Influence and What Resists Capture: The Bots Have Found Me

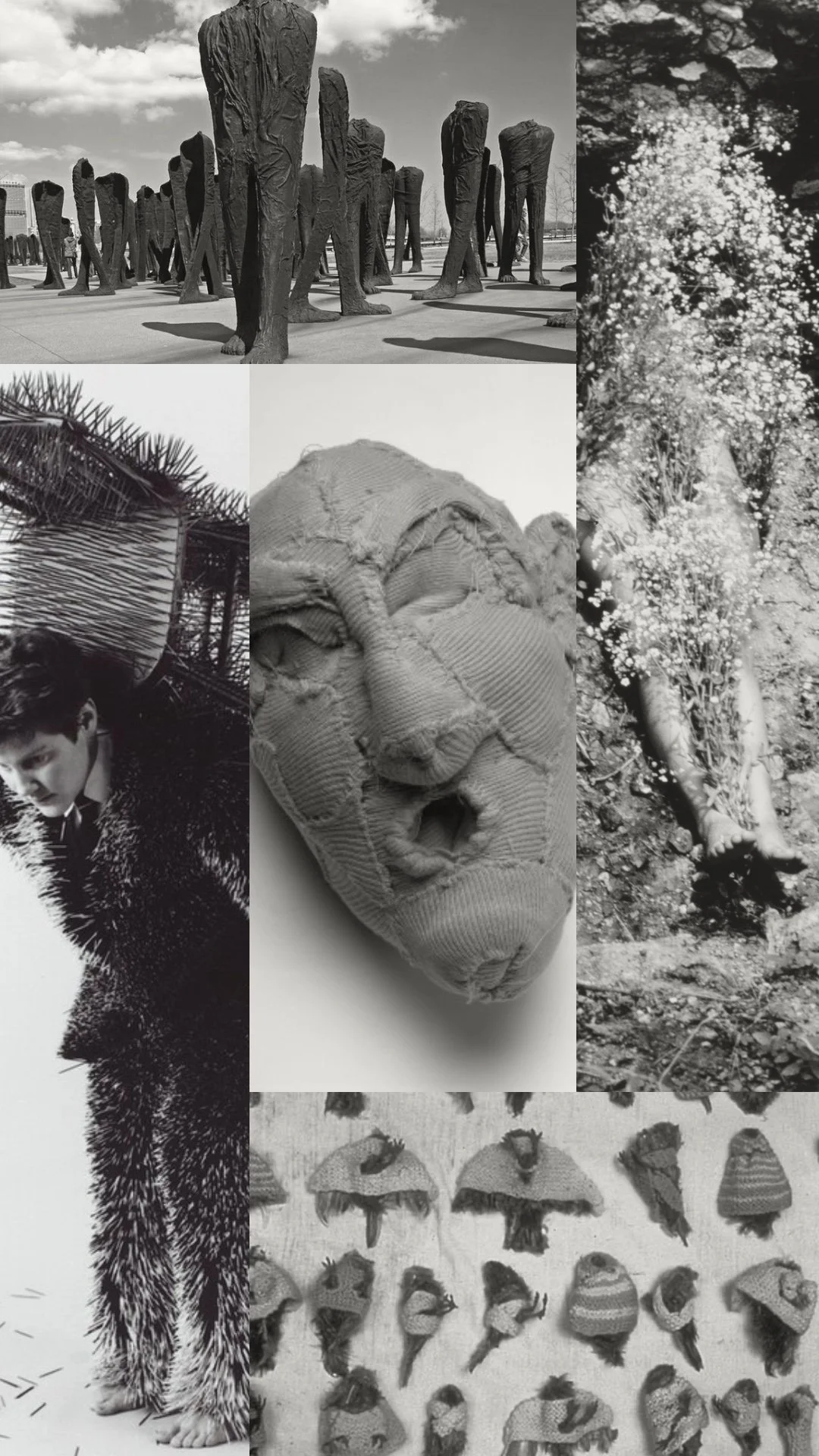

1) Magdalena Abakanowicz, Agora, 2006. 2) Ann Hamilton, body object series #13, 1984. 3) Louise Bourgeois, Pierre, 1998. 4) Ana Mendieta, Imágen de Yágul, 1973. 5) Annette Messager, Boarders at Rest,1971.

I was answering interview questions the other day, and one asked which artists have influenced my work. Many have, of course, but a few surfaced immediately. Some very specific works have stayed with me over time.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Agora came to mind, with its mass of headless figures that feel both collective and isolated. I remember stumbling upon the work while walking through Chicago’s South Loop, not long after it was installed. It was the first piece of public art (and one of the few :-/ ) that elicited a strong, immediate response from me. The metal figures drew me in like magnets and kept me there, as if I were walking through a maze. This was in 2006, shortly after I had moved to the city. It was a brisk, overcast day. My eyes were simultaneously dry and watery, but shining from what felt like discovering treasure. At that time, I had no idea who Abakanowicz was, nor did I know she was a fiber artist I would grow to admire.

I thought of Ann Hamilton’s body object works, where the body becomes an absurd object—part sculpture, part performance. The photographs stand on their own as beautiful works of art. Louise Bourgeois’s Pierre stands out for its refusal to be polite; its lumpy, weighted form is unafraid of being ugly, and in that ugliness there is a kind of honesty I admire about Bourgeois’s work. Ana Mendieta’s Imágen de Yágul remains vivid for the way her body merges with the earth, leaving only a trace. Her reference to death is elegant and tender. And Annette Messager’s knitted sweaters placed on taxidermied birds also hold a strange tenderness—domestic and unsettling at once.

What draws me back to these artists is not a shared style or medium, but the way their work speaks of the body, nature, the absurd, the macabre, the taboo. None of them are repetitious artists, yet their visual language is always recognizable to me. They are both expansive and distinguished.

While writing this, I found myself pausing over whether or not to include images. I’ve been thinking a lot about copyright and circulation ever since I noticed unusual spikes in traffic to my website. These spikes were too abnormal to be excited about. They were from a single country, China, paired with an unusually high bounce rate. These visits led to virtually no engagement, and they were all from a similar IP address. Bots. These visits are likely bots scanning and collecting information rather than human readers. Why has my website piqued the interest of bots and what will “they” do with the text and images they are collecting? Will this “data” —my artwork—be used without my permission? Probably. How? I don’t know.

This discovery shifted how I think about visibility. Images no longer circulate only among viewers; they are increasingly absorbed into systems that treat them as data, often stripped of context and authorship. The presence of AI has made this extraction faster and more opaque, especially for artists whose work relies on subtlety, ephemerality, or the body itself. Many of the artists who influence me worked with gestures and materials that resist capture. Mendieta’s work, for example, now exists largely through photographs, yet those images are only traces.

How do I speak about and document influence without contributing to further erosion, and how do I honor lineage while protecting the integrity of the work and my own practice? For now, my response is to move with care: to name artists clearly, to lean more on language, and to stay attentive to what is shared and how. And what do I make of the bots who now visit me multiple times a week? How do I protect my work, my vision? How do I resist capture?